Part two in this series in examining current and prospective future heavy vehicle regulation

Effective and efficient road access is essential for transporting goods and passengers. It is the cornerstone of ongoing economic competitiveness. Regulators must find ways to improve not only access to the road network but the efficiency by which goods and passengers are transported.

Vehicles access the road network according to prescribed limits which nominally reflect the roads capability to handle the mass and dimension of prescribed vehicles. These limits in many cases do not reflect the networks true capability or that of the vehicle.

There are many requests for access denied simply on the basis that road owners don’t want certain types of vehicles on their roads. It has nothing to do with the road network or the vehicles inherent performance characteristics but that the vehicle is called a B-double or road train – monster trucks. This is indefensible regarding risk to road damage and safety.

Streamlining processes associated with providing access to vehicles that require additional mass or are over dimensional is essential. The current notice system is unwieldy and cumbersome for both industry and the regulator. It could be easily improved by removing commodity-based notices and creating notices based on mass and dimension envelopes.

There are many notices for different commodities such as cotton and hay bales which have almost exactly the same requirements and conditions. By creating a mass and dimension envelope notice a vehicle would not be granted access based on the commodity being transported but the road networks capability.

Any heavy vehicle that complied with the mass and dimension envelope and the requirements and conditions would enjoy the benefits of the notice regardless of the commodity being transported.

The future of Regulation: Part 1

Productivity Improvement

The heavy vehicle industry hasn’t seen a general mass increase in the last 20 years. This is stifling productivity and impacting road safety by increasing the number of vehicles on road. At present the NHVR operates the Concessional Mass Limits (CML) scheme. The scheme provides for an additional 5 percent above the prescribed gross mass limit for the heavy vehicle or combination. Vehicles accessing the scheme must comply with the mass maintenance module of the National Heavy Vehicle Accreditation Scheme.

CML vehicles have access to the same route network applicable to the class of vehicle being operated, that is the same routes if they were operating under general mass limits (GML). Given that all road owners allow CML vehicles and that they operate without restriction what is preventing regulators from moving the GML to the CML? Providing an immediate 5 percent productivity benefit to the entire heavy vehicle fleet?

A beacon a light in the productivity space is the world-renowned Performance Based Standards (PBS) scheme. The scheme is 10 years old in 2018 and there are several issues to overcome if it is to continue to deliver productivity and safety benefits.

Allowing PBS vehicles as-of-right access to the road network would be one of the most significant benefits to the scheme. Providing recognition within the law for the most common types of PBS vehicles must be delivered.

National regulator

The National Heavy Vehicle Law is now five years old and there is still no indication from the Northern Territory or Western Australia as to when they will join the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator. It appears they are unconvinced that a national regulator can deliver the productivity and safety benefits they are delivering themselves.

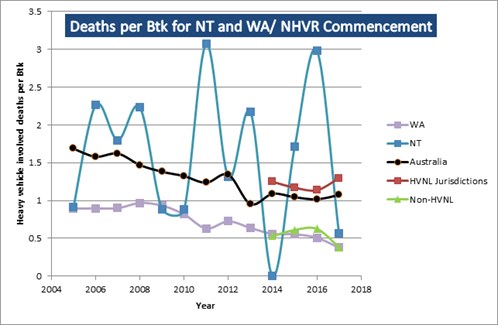

On the safety front there is some evidence that this argument is valid. The below graph provides details about the increase in total heavy vehicle deaths since the commencement of the NHVR and the continued downward trend in deaths in both Northern Territory and Western Australia.

It is much more difficult to assess the impact on productivity and this is work that will be undertaken by the Productivity Commission in 2019 but the regulator has no published information on how it has improved fleet productivity in the last 5 years, save information related to the PBS.

The solution

The complexity of the heavy vehicle regulatory environment is exacerbated by sharing responsibility for regulatory functions between multiple jurisdictions. This must end and soon. While responsibility, and therefore outcomes, are spread across multiple jurisdictions, no consistent vision or accountability as to how to address productivity and road trauma will emerge.

The Strategic Directions 2016 and Setting the Agenda 2016-2020+ are stepping stones to developing a vision of a truly national regulator. One which must articulate what it will be when it grows up.

What might the regulator look like in 30 years? There is a clear requirement for strategy and policy expertise to navigate and understand how to plan its future. As a safety regulator it needs to have responsibility or at least drive strategy and standards in every aspect of the heavy vehicle regulatory function, this includes driver licencing.

This is not to suggest the NHVR be responsible for testing or issuing licences, but it must be accountable for the standards by which drivers are tested and licences issued and the ongoing professional development requirements of drivers.

It is logical that at some point the NHVR become responsible for light vehicle regulation. The advent of autonomous vehicles and a body to regulate them at a national level is required. The NHVR can be well positioned to manage this function. It is a logical synergy and can deliver an array of productivity and safety benefits.

It is evident that the regulator has an extremely constrained budget which creates a definite road block to making meaningful headway on a raft of issues. The National Transport Commission is working on user pay model to determine how the future road network and enforcement of industry will be funded. Much of this is predicated on the decline in fuel excise due to more efficient engines, coupled with the growth of electric vehicles.

The most effective way to deal with the financial constraints is to have a regulator that does not own, manage or run facilities, employ on-road compliance or inspection staff but is focused on setting strategy, policy and standards by which it will assess industry compliance. It will be responsible for providing the assurance function that audits and manages the systems, processes and people who provide these services on its behalf.

The backbone of this model is that the emphasis is on ensuring that industry is voluntarily demonstrating compliance. The regulator is only intervening based on evidence that a risk to safety exists and utilises policy levers to create behavioural change through targeted enforcement approaches that address high risk non-conformity.

Only when we have a vision of what must be achieved, the goals established for improving productivity and reducing road trauma, can a pathway be mapped as to how to get there. Who is going to provide that national vision and when?

*Setting the Agenda 2016–2020 Strategies for a Safer, Productive and more Compliant Heavy Vehicle Industry, Page 13.